Metro chief reporter. Tottenham Hotspur and The Beatles fan. See also: http://aidanradnedgemetroblogs.wordpress.com/

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

Friday, November 17th. 12.30pm, in the air above Ethiopia.

“P.M.T.C.T, find out what it means to me…” – my suggestion for an Aretha Franklin-voiced Christmas single to promote Tearfund’s campaign for better “Prevention of Mother To Child Transmission” services...

A silly joke (always my favourite kind), but perhaps unusually this trip – now ending – has been studded with them, apparently flippant but necessary reflex responses to such otherwise-overwhelming despair.

An opinion poll reported on the front of yesterday’s Daily Monitor suggests seven out of ten children remain happy and positive in eight of Africa’smost crushingly deprived nations, Ethiopia of course included. Despite the abject poverty, it’s easy to believe of the irrepressibly eager kids all around.

But it’s a challenging context in which to guiltily glibly speak of “happy”, or at least “happier”, stories. Our re-visit to the Addis Ababa Medan Acts compound yesterday brought us face to face with two more HIV-positive (maybe the sole circumstance in which being “positive” is such a negative) – each tugging along their children, yet only one of the mothers consoled by their child’s health.

In one sense, 35-year-old Shewaye Hailu’s is the “happy” story, as her carefully-timed 200mg dose of Neviraprine during labour effectivelv shielded daughter Lydia from a deadly inheritance – the three-and-a-half-year-old girl now plays with ten-year-old brother Nathaniel, both (sorry, for now) unclouded by infection themselves.

But for all Shewaye’s relief and apparent tranquillity, she remains HIV+ herself, not yet severely-affected enough for ARV treatment but perhaps not far off. Hers, of course, is yet another distressing narrative – long detached from the husband of her first child, a hypocritical church elder who refused to accept any later involvement; probably infected by her cheating, previously-married husband who still refuses to be tested despite his telltale sinking bones and blistered flesh yet continued to force unsafe sex upon her until she finally walked out.

But, having planted between four and nine kisses upon each of us as greeting, she shrugs off any suggestion of being angry at her own fate – or her God – and instead talks up her prospects both working as a cleaner, and selling wheat and vegetable oil thanks to grants in cash and in kind from the helpers here.

It could have been rather different, however: “If my child had beeninfected because of me, I couldn’t have been able to cope with the stress and the agony. I couldn’t have survived this far – I’d have died some time back. The help I received is the source of my own survival as well as my daughter’s.”

How deep, then, must be the pain 25-year-old Mulumebet Bereket endures, even as her two-year-old daughter Tsion runs, plays, hollers, squeals, munches seriously on a handed-out Frusli bar, as the globular blisters sit like tears down the little girl’s cheeks.

Mulumebet, aware of her HIV status, had assiduously taken the 200mg pill as she began labour in her home, but was unable to keep the pill down, then was unable on arriving at hospital to explain to the medics she needed a replacement dose in time.

Tsion was born on the reception room floor – and, sure enough, passed the virus, the latest heartrending setback in a life that began with Mulumebet never knowing her separated parents; brought up, until the age of ten, by an older sister, but hurled out of home when said sister died; bumped from one unhappy, bullying home to another, and another, before even reaching her teens, as she struggled to find lasting work as a maidservant; forced into an affair with one employer, resulting in now-sombre five-year-old Mikias, born at 10am one morning only for his father to have fled by 3pm; persecuted by neighbours whenever lucky enough to find an all-briefly-rented room; often forced to spend days on the street without a scrap of food; brought to the brink of hanging herself with carefully-prepared noose and platform only for a timely neighbour to happen by her home...

Yet her stately, voluble storytelling has us flagging at the horror, more than it seems to affect her - the least we can offer are a fair few dollars for some of the handsome green-crossed, embroidered tablecloths and smocks she proudly spreads across the Medan Acts meeting-room tables.

The tributes to the Medan medics come not just from the patients/worshippers - it seems they have absolute faith placed in them by the appropriate authorities - both regional and federal.

Dr Fikir Melesse, the paediatrician in charge of the family department at the regional ministry of health, reveals all 31 HIV area projects in the capital are now under the control of Medan and a handful of other church-spearheaded NGOs - the politicians and officials seemingly satisfied retiring to the sidelines, especially after a pilot partnership with Intrahealth proved insubstantial to all and dropped after the obligatory year.

Amid the expected bureaucratic waffle, the mistiness of “priorities” and “strategies” and “objectives”, the good doctor does admit ignorance of how much exactly the state had invested into HIV healthcare - but also sighs ruefully, sharply: “You can’t imagine the discrepancy between, say, agriculture and health budgeting - we’re low down, put it like that...”

She also seems frustrated by both their dependence on outside intervention, and its limits - the lack of an effective co-ordinated response to the twin debilitators of HIV and food shortages, albeit expressed accompanied by a slightly startling image: “Malnutrition is the most important issue in an urban setting like Addis. People have nothing to do, nothing to eat, they have no blankets, so they start to make love - and have more children. What we want to see is both tackling HIV and at the same time combating malnutrition. Something too often we’re not even trying to alleviate. There are attempts here and there, even [even?] by Unicef, but at the moment I don’t think that’s anywhere near enough for Addis.”

So - more food, more donations, are needed - but surely, too, better focus and organisation? Often the problem - problems - have looked so vast and forbidding, any response is bound to look a little futile by comparison. But these lesser or greater acts of compassion and practical help, as seemingly exemplified by the likes of Dr Henok and the Medan teams, at least act against some of the all-too-easy cynicism.

It seemed hard to believe, but even the ever-beaming Dr Henok the other day admitted to a brief, recent attack of despair and foreboding, as the full implications of enforced changes to the PMTCT drug regimes began to dawn. Recent studies have shown up alarming limits in the efficacy of the 200mg single doses - only thought now to have, at best, a 50 per cent chance of preventing infection and, as Mulumebet’s plight illustrated, subject to grim mischance. Now, a two-pronged approach will combine Naviroprine with one of several specialist combination treatments - to be prescribed once a day for the final 60 days of pregnancy, and for a further month after birth.

Dr Henok and his old college comrade Dr Melesse are optimistic about the improved chances of success - but the estimated cost of administering to each mother, from the January 2007 changeover, will soar from $10 to $90. Tearfund’s choice of Christmas appeal has just become, perhaps quite unexpectedly, even more worthy and needful...

(The less said, perhaps the better, about our final, anti-climactic encounter of the week, and our second with a supposedly relevant Government official - a hapless number-cruncher and IT assist in the federal ministry of health who, beyond insisting mortality rates were “getting better” albeit without the assistance of specifics, seemed apologetically incapable of sharing any figures at all, or opinions - save for explaining his sideline work of chairing the new “health infomatics association”, only to dry up, baffled, when I straightforwardly, maybe a little sarcastically, asked him how this would actually affect a suffering, struggling individual with HIV. Dr Henok did come to his - and our - rescue by entirely reasonably pointing out the benefits of computerised, comparative data, file-taking, checks and tests-recording, and on and dully-but-worthily-if-belatedly on...)

This is where I left off scribbling, on the flight home last Friday, my eyelids clamming shut and “The Devil Wears Prada” about to start up for the second time… telling myself I could come back to this in between scrawling and typing up, and produce a finer, more thoughtful and climactic conclusion. Sadly, I couldn’t and haven’t and won’t, having no doubt been self-indulgent and turgid enough so far. On returning to work, it’s been tricky to know just how to respond to the inevitable questions of “How was Ethiopia, then?”m guessing the interrogator is neither expecting a breezy “Great, thanks!”, nor wanting a lengthy, agonised description… So far, I’ve resolved to stick with such thus-far-and-no-further, yet still a little emotive, terms as “Fascinating”, “Intriguing” and “Eye-opening”.

Maybe even a humble “Humbling”.

And it was, all those things and many more. Now to batter these overwritten ramblings into something approaching concise common sense by Friday week, World Aids Day…

The End.

For now...

Thursday, November 16th, 2006. 7.10pm. Hotel Desalegn, Addis Ababa.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, as our last evening in Addis Ababa looms, I sit in a hotel room suffused with the overpowering aroma of rich Ethiopian coffee – four 500g bags of roasted, one 500g bag of ready-to-cafetiere ground coffee, this blend apparently dubbed "God’s urine" and bought the intoxicating coffee emporium of local providers Tomoca. Now all I and my Christmas gift beneficiaries need is a grinder...

A kilo costs 41 Birr – about £2.50, and about what you’d pay for a bland mere mug back home in Starbucks or Costa Coffee or wherever, places that have always irritated me – especially, selfishly, at the thought of credulous customers spending so much on a cup, while nevertheless complaining about the slightest price rise among much more valuable-for-money newspapers…

Dr Henock was astonished, even more justly, to hear of such places – coffee farmers among his Addis congregation sell their finest flavours for just 4 Birr, or 25p, per kilo. Perhaps a fair trade opportunity in the import-export market is here for the cultivating...

For some illuminating overviews of the city slums, we were taken to the tenth floor of a rather sleazy-feeling hotel – dubiously relying on a creaky, cranking, doorless, doorless dizzy-making lift. On eventual arrival at the top, there appeared to be little to see this side of the hazy mountains, between the brutal useless towerblocks - just desolate wastelands of tin sheeting.

Except then, there are appeared a few flickers of miniscule movement in the crevices – peering more carefully, I could just about pick out laundry-hauling housewives, ball-chasing children, scraggy mangy dogs. Of course, these were the shanty "civilisations" beneath the metal sheeting, stretching as slums, as one, across the city sprawl. And still Addis keeps spreading – not vertically, as the Government planners might desire, but horizontally – ever wider, yet always looked down upon.

Wednesday, November 15th. 9.40pm. Hotel Desalegn, Addis Adaba.

Coffee courses through Ethiopia like lifeblood, rich and reinvigorating. Solomon claims the country gave coffee to the world, hence the region now named Kofa. It certainly seems to play an even most essential, characteristic role in daily life than does a cup of good old English tea back home.

Coffee is the country’s second main export, behind only oil – and Ethiopia is now the leading coffee producer on the continent, with exports up from 95,000 tonnes in 1991 to 146,000 tonnes 12 years later. Now, as well as satisfying – then again stimulating – a thirst, coffee may even be easing some of the suffering – and divisions – wreaked by the HIV epidemic.

We had already been struck by the strength – and sumptuous, spicy flavour – of Ethiopian coffee, as served at and after every meal or meeting, and urged Solomon to help us find and buy plenty of freshly-ground to take home for presents and personal indulgence. He should know his coffee beans – after all, he has been drinking the stuff since the age of three.

But this morning in Nazareth we got to take part – albeit tentatively, tangentially – in the time-honoured tradition of the Ethiopian coffee ceremony, this one with a twist, Apparently, to drink coffee entirely alone is seen as a grievous anti-social offence. Instead, people habitually gather, often in a specified host’s shouse, to slowly savour the grinding, the boiling, the pouring of at least three rounds into dainty round cups, all the while discussing in detail the latest local issues of importance, family news, any other business. A little like a Women’s Institute morning meeting, albeit with a little less gossip and plenty more coffee (and sugar, stubbornly gritting the floor of each cup).

The Kale Heywet/Medan Acts people have hijacked these ceremonies to an even greater good, however, encouraging identified HIV sufferers to play mein host – and invite in all the neighbours, including those who might have been most hostile or suspicious, evening imagining a risk of infection from simply sharing dwelling space, crockery or basic conversation.

Instead of resentment and alienation, these social occasions have apparently instead fostered greater understanding, advice-sharing and mutual support – and our experience, alongside about 20 bolshy but gracious women cetrainly felt like very emotionally healthy fellowship, even if the coffeepot did take an age to be ready and even at one point explosively overflowed. (Tch, typical women, too busy gassing to keep paying attention…)

Here rises village elder Etagehn, recalling how she recoiled upon first hearing of daughter Tigist’s diagnosis, first blaming her and "acquitting" the husband – then dragging daughter to a series of re-tests, refusing to accept the awful reality. "I said, this can’t be true – it’s just too shameful."

Perhaps the coffee ceremonies can’t be entirely credited with changing her point of view to today’s acceptance and concern. But Etagehn insists such displays of community backing – and the breaking-down of barriers and misconceptions – helped reconcile the pair, ahead of the TB and skin complications that made more practical medical help a necessity.

Now Etagehn tells the rapt gathering: "If I’d stayed so angry with my daughter, she might have been dead by now, But she’s here, a lot happier and strengthened."

Here speaks up tearful Tirunesh: "I used to be afraid to come near other people, until someone told me about these ceremonies. They really helped me get away from my fears. Sometimes I don’t even feel I’m living with the virus – I almost forget. I come as close as possible to forgetting my problems, since I came into contact with this real fellowship. The fear has gone. I feel at one with the community."

Tales are told of HIV+ victims being thrown out of doors by their own families – forced to drink water from discarded tin cans or ketchup bottles, eat only off unwanted, cracked plates. But at least here, all can sip as one, suffererers and non-sufferers, grandmothers and even a few tastebud-opening toddlers. One little boy is almost crunching his cup as he slurps down every last drop. Tigist’s son, in contrast, steadfastly slumbers in her arms throughout.

These awareness-raising coffee ceremonies – "Buna Tettu" – won Kale Heywet a "Red Ribbon" award at this year’s UN Aids conference in Toronto, one of 25 projects to be honoured from a "shortlist" of 517, only three from Africa. In the last 18 months, the scheme has reached 1,593 bedridden patients (65 per cent of whom are female), and involved 7,000 people in HIV discyssions.

Among those tucking in this morning were a few familiar faces from shortly earlier in the day, in the half-hectare fields of the Nazareth Medan Acts base. (I’m not quite sure how these women beat us down to the open-air ceremony, having actually watched us drive away in advance from the Medan HQ).

Addis Ababa and the route eastward may be known as the "high corridor" of Aids in Ethiopia (though the climate in the Muslim-dominated eastern areas seems to be too scorching and unbearable for any notable UN or US aid efforts as yet). Nazareth is especially vulnerable to depressingly high infection rates. The smooth-ish, recently-completely main road that allowed us to cover the 100km route in about 90 minutes is also regulatly covered by high levels of transit truck traffic, to and from both the capital and Arabic/Middle Eastern neighbours. Nazareth is a major magnet for both prostitutes and prospective clients – or "commercial sex work", as our guides here so consistently, if a little coyly, describe this field. The many factories in the area also draw in hordes desperate for work, while even tourists are tempted – especially by Nazareth’s hot springs.

The Medan Acts, by some self-professed "miracle", secured from the Government a patch of land and buildings on the outskirts of Nazareth, where they base not only their educative and preventative work – involving 25 local schools and 23 churches – but also provide plots of soil for HIV+ women to work, and ultimately enjoy the fruits – and veg – of their labours.

Each woman, just about robust enough to toil thanks to ARV treatment, is gifted between three and ten plant beds to till tomatoes, peppers, lettuce, onions, carrots and cabbages. Should they harvest well, the 70 women signed up so far can take home some for themselves to eat, some to bed down in their own optimistic gardens, and some to sell on – indeed, Solomon later proves a satisfied customer as the coffee gathering breaks apart.

Selmawit Benti is a former prostitute – sorry, commercial sex worker – who may look relentlessly downcast and reluctant to peer up from beneath her pink net headscarf. But she is determined to make this most of this opportunity, despite having to struggle her way from the other side of the city. Orphaned and abandoned as a child, she dropped out of school early, journeyed her from Dredor 300km away, and could only find work – and quick, easy cash – in the bars and brothels. She was diagnosed HIV+ four years ago and, as seems to be a common symptom, first needed serious treatment for incipient TB.

After spending a gruelling two years in hospital, she was advised to seek support here – and now, after three months of planting, is eagerly awaiting her first full, and imminent, harvest. In the longer-term, she aspires to become entirely self-reliant – and to see similar schemes springing up just as bountifully across the country.

"They need more support, though," the newly-wise 25-year-old cautions. "This was all set up with just 60,000 Birr [about £3,750] for the whole project, and that all went straight away. We’ve all had to pay for things as a group, like the water buckets. It’s a good project, but it could be strengthened."

Sidling our way, or at least in the crouching photographer’s direction, 25-year-old Hirut Semu sets down her hose long enough to explain how she has so far survived not just HIV, but a suicide attempt in the depths of newly-diagnosed despair. After her husband died of Aids, the penny dropped that she too might be infected – and the unwanted confirmation came as she was pregnant with a son, now four.

"I was terrified – I really wanted to kill myself," she says. Hirut downed a stomachful of Malathion, a toxic chemical used to kill rats, but concerned neighbours managed to rush her to hospital in time for her life to be saved.

Happily, if surprisingly, her unborn child survived as well, though it was three months before Hirut could be discharged from hospital. Her digestive system is still warped by the after-effects of the poison, but ARV treatment has bolstered her enough to join the women in the fields.

"I’m relieved from my worst anxieties now. When I’m working here in my garden, I forget all my old traumas and I can hope to live a better life in future."

And so to share such tragic pasts, and defiant futures, over those steaming, stimulating cups of coffee.

On the long drive hotel-wards, Solomon pessimistically ponders the the condition and contradications of Africa – "We blame the old colonialists, byet Africa has subjected itself to new, local colonialists – our own tyrants" – plus the prospects for free and/or fair trade. We also ask whether or why African couldn’t exert more power over the coffee markets, in the way the Middle Eastern states can do over their oil. For Opec, see an Ethiopian-led Copec. But for now it seems the technology is too inadequate, the corruption too corrosive, the lip-service from our developed world too pathetic, dishonest about its intentions.

Ethiopia, literally meaning "the burnt-faced peoples", was once the byword not for famine and pitiable super-poverty, but instead the greater expanse of sub-Saharan Africa, a progressive civilisation pushing beyond the Middle Ages more progressively than many of those nations now Western powerhouses. But subsequent, seemingly-endless years of conflict, destruction and neglect have come to this – according to a strangely-precise calculation from Solomon, Ethiopia has enjoyed just 105 years of peace.

Outright colonial rule of the country may have been restricted to five years of Italian control during the Secomd World War. But bloody territorial disputes, still straggling today, with the likes of Sudan, Eritrea and Somalia, have crippled Ethiopia’s chances of effectively addressing such grinding poverty.

These still-green expanses trundle by – the slipshod painted Pepsi signs; the singular "Spare Part Garage"; a bumpy cross-section of the nation’s 350,000 trucks – a few overturned in a glassy, blood-soaked mess hopelessly remote from any ambulance or hospital help; and handfuls and hundreds of the thousands and millions of "burnt-faced people" simply walking onwards, somewhere.

Monday, November 20, 2006

Wednesday, November 15th, 2006. 6pm, on the road back to Addis Ababa from Nazareth.

“Selam – hello – I love you!” “Selam – hello – I love you!” “Selam – hello – I love you!”

And still the kids keep coming forward, crowding around me with beaming faces and skinny arms outstretched to shake hands – several faces I recognise from handshakes just a few moments earlier, coming back for more.

“Selam”, I reply, having finally learnt and remembered just one word of Amharic, and tentatively brandish my cameraphone a couple of times in the direction of the leaping, waving, squealing swarm of children.

Marcus the photographer and I certainly caused a stir as we delved through a Nazareth village market, taking photos – and making a sudden celebrity – of 67-year-old grocery kiosk-keeper Khadija Mohammed. She patiently “sold” and resold and resold one bunch of browning bananas to a ragged yet graceful pretend customer, as Marcus snapped away beneath the booth’s low counter, having crawled awkwardly through a catflap-esque entrance at the back.

The shop can have been no bigger than the homes we saw yesterday, only this had relatively “rich” pickings spilling from the shelves: Glory biscuits, Fegegta crackers, Aladdin’s Constant mystery mixture, Scissors safety matches, more familiar yet miniaturised bags of Ariel Gold Plus washing powder, and a deep barrel of bright red lentils.

A few paces ahead of her stall, a small but severe-looking boy guarded a sack of corn, underneath a billowing brown canvas and alongside an older man who would occasionally stand and flourish a long thin stick in mock anger if the surrounding swells became too boisterous. A younger, slightly smarter man was on constant walkabout with a half-brush, half-whip in his right hand, lightly slapping the legs of any curious child who wandered too close while walking home from school – albeit never with much malice or backlift.

Their clothes may have been long-worn and spare, but they range from finely-arranged shawls and gowns to freshly-faded modern sports sweatshirts – sad to say, more often than not showing off an Arsenal badge. As here in Nazareth, 100km from the capital, so seemingly across Ethiopia – Solomon confirmed the suspicion, this is Gooner territory, save for the occasional knock-off top preferring Barca (10 Ronaldinho) or Manchester United (8 Rooney).

Such familiar fashionwear contrasts smartly with the all-pervading poverty and dated, crudely painted eyesores above eye level – here in Nazareth perhaps more so than even in Addis Ababa. Here, ramble goats, back-breakingly burdened donkeys, emaciated horses with savagery in their eyes. In Addis we had seen men randomly sprawled asleep on the kerbsides – across Nazareth, diagonal canvas strips mark out barely-there excuses for “homes”, more claustrophobic and debasing than a dog’s kennel.

Children seize amusement from riling a pet goat whose back foot is thinly tethered to a tree – swiping his horned head with a couple of quickfire volleys, only sometimes provoking enough of an effort to buck and barge in vain. (If the sight reminded me of the scene in Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop, and the hotel’s resentful pet goat who must inevitably escape from his ties in a fictional, factional Abyssinia-alike African nation-in-turmoil Ishmaelia, at least we were spared this goat’s eventual vengeance.)

Khadija’s small success – and may today’s attention hopefully give business a decent little boost – offers a sign of how people here can be helped to help themselves. The Nazareth Community Development Project, since its inception in June 2002, has enrolled 2,400 women into its “income-generation activities” – grassroots collective groups offering funding, business training, pooled profits and communal savings schemes for the “poorest of the poor , invariably the town’s women, engaged in such activities as embroidery, weaving, cattle-fattening, vegetable oil-mixing, sheep-rearing and engura-baking (enguar, the sour bread that is a beloved national staple, despite looking especially unappetising to us – rather resembling a Swiss roll of soggy concrete, or a furl of sloppy, paste-mired wallpaper – and tasting not a lot better. Ah, but “give us this day our daily engura”, our hosts cheerily implore – and we, equally cheerily, oblige.)

The IGA groups – split into SHGs (self-help groups) of between 15 and 20 people, and CLAs (cluster level associations) of eight to 12 SHGs – are now in the black to the tune of 487,000 Birr in savings – about £30,000. Funding for individual or group initiatives comes from members’ own contributions (20 per cent), Tearfund (ten per cent), the Kale Heywet church (ten per cent) and Dutch-based charity Dorkas Aid International.

As might be expected, especially in such a patriarchal society, many men were initially suspicious of such a women-led project, fearing – or, at least, dismissively claiming – the meetings would be little more than idle gossip shops. But as the money began trickling in – 100 Birr on a good day for mother-of-six Khadija, for example – so they started seeing a sunnier side. Now, one woman rejoiced: “My husband is the one who cleans the chairs every time we have a meeting here ahead.”

Although we discovered Khadija was HIV- - not too helpful, after all the photos, for our Aids-centred coverage; ah, how cynical – and the scheme is for the benefit of everyone and anyone, co-ordinator Mekonnen Kelsede explained how HIV+ women had much to gain – by participating, and empowering themselves, and also as other women boost their own livelihoods enough to contribute to communal care. Meanwhile, spin-off schemes involve building much-needed new homes, clothing children, improving – or, indeed, introducing – literacy and numeracy.

It could even seem a throwback to – or long-awaited implementation of – pure Communist principles. That is, had it not been for the over-indulgent sprinklings of business jargon – “capacity-building”, “targeted beneficiaries”, “economic stability”, I ask you...

All of which would no doubt be lost, for the foreseeable anyway, on the little kids now extending their palms for a different purpose, as we clamber into our van after taking our farewells.

“Money! Money!”, the understandably ask of the rich white men all of a sudden in their midst, potentially wielding power or patronage over them. But before we can even awkwardly, properly respond, our driver is spearing into second gear, Solomon shooing the last hordes away with barely a glance, and we’re literally lost in a cloud of dust.

What can you do?

But then again, what could they do? “Money!” “Money!” Well, why not...?

Sunday, November 19, 2006

Tuesday, November 14th, 2006. 5pm, Hotel Desalegn, Addis Ababa.

Smart, pristine pink new apartment blocks are rising from the rubble in the Tele Bulgaria sub-city, a rare display of modern-day development and optimism – and pretty much misleading.

Every apartment so far stands empty– save for a tottering stepladder glimpsed through one darkened window. And getting anyone able to afford to move in might be a momentous challenge – it looks tricky enough to simply remain in one of the squalid rusty shacks that make for “accommodation” (a generous term indeed) down below, next-door and across the capital.

One of these useless blocks stands as a cruel backdrop to a jumble ofunsafe rocks, low-flying clothes-lines and patter of traipsing children andmice-sized kittens leading into the unhappy home of bed-ridden Aids patient Mikre Mesele – dank dwellings in which she may have just four more days,with the prospect of worse uncertainty ahead.

I don’t think I’ll ever quite forget the first moment of stooping, stepping in. Even by all expectations of Ethiopian poverty and squalor, this is something else. The shack is in darkness as we struggle in, barely room for Mikre’s bed upon which she can barely be seen, and even then looking moredead than even barely-alive. Another bed lies at a right angle, astonishingly sub-rented out by Mikre to raise a little desperately-needed cash – while the merest scrap of hard flooring is all that serves as a painful resting-space for daughters Betamariam Selshie, nine, and five-year-old Alemayhu.

A crackling lightbulb, dangling across the room on a rickety wire, gives a flicker of vision, as Mikre’s frail frame arches an inch or two up from herpillow, croakily sharing with us how her landlord has given her four days to leave this hovel for which she pays 80 Birr per month (about $10 – and a rip-off at a tenth of the price). He apparently wants to renovate the place– but this is surely his second attempt to evict Mikre purely for her HIV status, after only an indignant neighbours’ revolt forced him to back down shortly after Mikre’s diagnosis six months ago.

She could never afford the higher charges he is proposing – as things stand at the moment anyway, the rent leaves her with just 20 Birr per month from the grant handed over by the capital’s – and the church’s – Medan Acts programme.

Agonisingly raising her head against the old-newspapers-matted tin wall, an improbable “London-New York-Paris”-sloganned sports bag perched somehow above her, Mikre can only frown as school-uniformed Alemayhu bounds blithely inside, before just as instantly chasing a kitten back out again.

“Even before I became ill, everything was very difficult and complex,” Mikre explains. “Sometimes there were days when we had to go without any food at all. WhenI could get hold of something, we’d eat – if not, we couldn’t.”

Life was made more arduous when Aids claimed the life of her husband three years ago. Like many of the people we meet, Mikre appears to have left most of her family behind in distant countryside, migrating to Addis in search of work, in desperate expectation of a better life somehow. Twelve years after travelling 650km from Gondar, now 25-year-old Mikre can only depend on the daily calls of home carer Sisaoibeyene, one of a dwindling band of tireless, unpaid volunteers. The Medan intervention at least means fewer days of starvation, as Sisaoibeyene bakes a daily disc of loaf, while the children have also been kitted out with school uniforms and packed off to their lessons.

Mikre was married for eight years before her husband’s death – suggesting she was just 14 when they wed. He was the main bread-winner – or‘bread-owner’, as Solomon translates it, a transitory moment of mild amusement – making his plunge into bed-ridden torpor an even more crushing setback. Yet again, like many we encounter, Mikre appears incredibly philosophical and unself-centred about her plight.

“I was extremely saddened by the situation – not so much because I was afraid for myself, that I would be infected, but that the kids would go even more without – about our whole poverty and style of life, more than my husband having the virus.”

After realising she too was positive, Mikre now spends her days lying helpless, unable to stir enough even to boil a rusty kettle or cover over the cat-mess-mired plates scattered aside.

“At first when I fell ill, I was really very upset – I lost all hope, Ididn’t have the energy to go out and get something for the children to eat. But after the project started helping me, my hope renewed a bit. I just can’t lose all hope. There were times I felt so bleak – I just didn’t know what to do. But I’m not personally worried about my own situation, about myself – I just heavily regret I can’t really do something good for my children. I’m worried about their future. People in foreign lands need to really focus on our children.”

The past seems to be something to be forgotten without fuss – from the bloody repression of the 17-year Communist era, to the loss of individual loved ones – to the signing of your own HIV death warrant

Two impassive portraits hang lop-sided above Tariku Leta’s bed – the faces of the parents who died within a month of each other this summer.

But ask 15-year-old Tariku or 12-year-old brother Girma about their recent losses, and their steady-eyed replies are all about how they are coping with the present – and preparing for the future. The pair have had to grow up quickly, momentously, during the past year, now living alone together in one cabin while partitioning and hiring out their parents’ old room next-door to raise a little rent.

Girma still goes to school – though he has returned now for lunch after an unusually-inactive morning. Tariku has dropped out, and juggled such jobs as shoeshine boy, carpenter’s assistant and sheet metal worker to pay the family’s way. And while Girma still looks a baby-faced boy, Tariku has the fixed gaze and severe voice of someone many years more mature than his actual age.

“Because of trying to make ends meet, we haven’t really had time to play and enjoy things with the rest of the community kids round here,” he shrugs sombrely. “We didn’t get to enjoy childhood like we should have done, like others do.” Do they have any pleasures or distractions at all? “No, none. We’re leading a serious life of older people.”

The extended family lives 125km away, placing the burden of their parents’ care formidably onto the meagre shoulders of the two boys – and increasing the isolation as they mourned.

“When we lost our parents, we lost all hope. Our lives were completely shattered,” recalls Tariku, who takes his name from the father who died aged 47. Mother Ananetch was 35 when she died in May.

“In the past, we never really cared about anything – we never worried about where breakfast, lunch or supper came from. Now we have to cook forourselves – and earn enough money to buy food in the first place. Life has completely changed, and things are really getting more expensive,especially as we grow.

“I feel responsible for my little brother – I have to make sure he goes to school, for the sake of his future. But for now, only one of us can earn. Iwork in a metal shop but some days, like today, there’s no work for me to do – and no pay.”

A smattering of stationery sits in the corner, supplied to studious Girma by the people at Medan. Tariku has also been promised some wheat, and hopes soon to sign up to an income-generation scheme – typically, involving a $100 grant to start selling a little home produce, whether agricultural or arty-and-crafty.

He and Girma also have higher aspirations – both want one day to become doctors, a legacy of seeing their parents suffer so: “We want to be doctors because we want to participate in the kind of ordeal our parents went through. We want to make sure these things don’t happen to other people.”

Tariku quickly checks himself, loath to dwell too long on those dying days: “The past is gone. Our parents are no more with us. It’s pointless for us to think about them. We’d rather choose to concentrate on our current situation. We don’t really spend any time thinking about the past.”

Yet there are clearly some moments when bleaker memories can steal upon them unawares, often under cover of treacherous sleep. Yes, there are bad dreams – bad, because they seem good, softly-spoken Tariku allows: “Sometimes I find myself in some kind of nostalgia about our past lives, when both our parents were alive. And we get upset, reminded of the good lives we used to lead.

“That’s why we try not to think of it at all.” Men sadly forced into maturing ahead of schedule – and yet sometimes still, boys will, and must, be boys again.

Senait Dender’s home is no larger, nor any more luxurious, than a toilet cubicle – in fact, that’s what it was before a relative made the merest of alterations to allow her and baby son Yonas to move in. A sunken bed, a stiff sky-blue shawl on the wall and – well, that’s about it, a grubby baby’s bottle in the corner aside.

Before coming here eight months ago, the pair were sleeping in the streets under a flimsy blanket, having being thrown out of her uncle’s home by a mistrustful aunt and a vindictive landlord’s ultimatum: either the HIV girl goes, or the whole family.

The sight of huddled-up Senait, 22, dripping tears over Yonas in their mudbank-set settlement is sad enough – but her back-story is even bleaker: raped at 14 by the head of a household where she worked as a babysitter; forced to give up the resulting child, now nine, to a faraway aunt; infected with HIV at the age 18 by a here-today-gone-tomorrow boyfriend; then later deserted by her husband, the father of Yonas, after being laid low by HIV and opportunistic diseases such as TB.

Her husband, a soldier, initially assured Senait he was being transferred to serve in another part of the country, only for her later to discover him living elsewhere in Addis Ababa still, wanting nothing to do now with his wife and then-six-month-old child.

Yonas keeps crawling, calling for a scrap of notepaper, happily banging a stray pen against our pads, occasionally squealing, on the verge of tears and a tantrum that don’t quite come. His mother taps her fingers on his head in admonition, jabs the filthy-teated bottle into his mouth and awkwardly adjusts her rheumatism-riddled legs folded underneath her – too weak to take a walk outside, to show off her son down the scruffy-kiosked pathway.

Yet she insists she is through the worst of her sickness, having responded encouragingly to TB treatment and now a month into her course of anti-retroviral drugs: “I hope and pray that God might give me my full health back, so I can work and raise my baby myself. I have very strong hope and faith because a couple of years ago I was so ill, people were expecting me every day to die– I was virtually paralysed. If I’ve passed through those difficult days, even now I have hope of being fully healed. I’ve been ten times worse than this.”

But still, but still… “The worst days are at holiday times, like New Year or Christmas, when I see people enjoying themselves, rejoicing, visiting each other – and I find myself closeted in my room, with no one coming to visit me. Or at any time if I see or hear someone laughing or having a good time, I remember the good days I had in the past. When I could work. When I could earn my own living. When I had my dignity. Those days come back to me, and it’s very difficult. Even when people bring me food, it doesn’t taste good because of the state I’m in.”

Ah, but at least she smiled for the first time as we handed over a couple of rolls left over from (an inevitably guilty-feeling) lunch – having first checked with helpful Dr Henok whether to offer would be appropriate. (“Appropriate”? What an awkward and stupid sense of complacent Western“propriety” – hand them over, and let her and baby tuck in, for goodness’sake Aidan… He didn’t say that, of course…)

We left Yonas happily munching his surprise “treat”, and bump back to the hotel – through Confusion Square, the oh-so-aptly-nicknamed expanse of traffic chaos that makes Piccadilly Circus look like a deserted country highway; past the Medan Acts base where this morning factory worker Daniel Mekonin was a shivering bundle of nerves as he faced an HIV test, only to stride away relieved and thumbs up to us 20 minutes later, one of the lucky ones; past the “James Bond tailors” and the “Snow White laundry”, the traffic lights where a frantic wanderer raps on our windows and apparently angrily accuses me of being a Chinese billionaire exploiting his Ethiopian slaves (“Every country has its madmen”, Solomon sighs) – back to the all-the-roomier-now hotel room, to ponder, touched, on life’s shocking lottery.

Monday, November 13th, 2006. 6pm. Hotel Desalegn, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

"I have to be satisfied, just prolonging someone’s life a little..."

Hmm. Let’s start with the simpler perceptions, maybe to ease a little less awkwardly into the trickier. There’s a deckchair on the balcony, and a furry soft bed and long-drawn bath in the rest of the room. Across the street, a well-meaning European Union office flutters a flag promising “We believe in partnership”, as toy car-resembling baby-blue-and-white taxis wait languidly for any spare fares.

Further down the street from this cosy-ish, Westerner-oriented hotel, broken barricades of corrugated tin occasionally back away from garish, makeshift market stalls selling scraps of cloth, slabs of greasy red meat or the ever-essential bottles of water. Rising unsteadily above there might be a token attempt at a modern-day building boom, a half-formed monster of concrete dominated by tree-twig scaffolding and more resembling the blasted-out skeleton of a multi-storey car park.

A few jam-packed white vans veer across and alongside the occasional cab fortunate enough to find a paying customer, but the pedestrians comprise the heavier traffic, heavily bearing on shoulders a haul of fruit, a swinging timber ladder, or a a swaddle of shawls that must surely house a baby somewhere inside. Modestly paved and signposted highways suddenly swerve into rocky dirt tracks, the only coherent clues offered by shoddily-plonked French language pointers for invading foreign ambassadoires.

So, here I am in Ethiopia, that apparent by-word for starvation and suffering, pity pity and yet more pity. Caught in an uneasy clash of instincts, between wanting to project a more optimistic, forward-looking, famine-downplaying image - read all about it, the latest trade deal signed with, say, China, or France, in the parched-dry Government-led propaganda Press - and yet of necessity acknowledging the many, many human catastrophes every day, every where you look, thanks (thanks) to relentless epidemics; never-ending shortages of essential supplies, sanitation and medication; corruptly-misspent millions; and tokenistic international ignorance.

The Ethiopian embassy in London complains about the “unhelpful”, “negative images used by the media”. Solomon, one of our guides for this Tearfund-led trip, bitterly points out footage of the 1984 famine is still being passed off as present-day by some media organisations. There are the rich-ish coffee, cotton, sugar and gold to be mined here, the recent surges in cereal production, coffee exports, school access and attendance…

Ah, but then there are the doomed babies’ faces and fragile, flailing limbs - or the actually-older children yet so riddled with disease they could easily pass for newly-out-of-the-womb. These are the harder to see, to think of again afterwards - the in-and-out-and-in-again patients at the Zewditu Memorial Hospital - a former US mission facility, later confiscated by the 1974-1991 Communist government, yet now hailed by this regime as a national flagship, despite looking and feeling more like a grim, neglected old council estate - stale air and despair struggling through each cramped corridor and narrow crowded staircase. Some 600 children are regularly being treated on the mould-encrusted wards, where waste bins overflow with used needles and inter-mingling gunge.

Here, heartbreakingly, is two-year-old Mersi Kassahum, a chubby, uncomprehending face on a bizarrely barrel-chested torso yet a stick-spindly pair of drip-fed legs - HIV+ just like 23-year-old mother Nardos, both condemned to the disease by a father and husband long since fled, leaving them and a ten-strong extended family abandoned on the outskirts of the capital.

Nardos seems jarringly philosophical, even cheery as she poses patiently for necessarily-posed photos - but there also seems a tinge of denial as she insists: “I don’t want to really worry very much about HIV. What’s done is done. So I have to live with it, for myself and my daughter. This is the only outlet that could mean my child survives. It’s not important to worry about something that’s already been done. It’s not worth worrying about my husband now he’s left. There’s nothing I can do about it.”

But the unstinting aid workers out here are determined that something, much more, can be done - especially before infection, before it’s too late. Prevention of mother (or parent) to child transmission seems to be the keynote theme this year for Tearfund, especially in the run-up to World Aids Day on December 1.

One 200mg tablet of Neviraprine for the mother as she enters labour - plus a 2mg/kg dose of the same for baby up to 72 months of delivery - can apparently vastly reduce the risk of an HIV infection being passed on. Such treatments can cost less than $10 per mother - yet many still go without, in a country of between 180,000 and 200,000 HIV+ pregnancies every year and up to 80,000 babies born with the infection. Some 25,000 children died due to Aids last year, according to Ministry of Health records - but many believe thousands more are going unreported.

If a mother is HIV+, her unborn child has about a one-in-three chance of inheriting the infection - of the 35 per cent who do, 15 to 20 per cent are infected during pregnancy, up to half during delivery, and about 33 per cent through breast-feeding. The dangers linger for some months.

So much for the statistics. Mersi was here for her sixth admission to hospital. In another white cage bed, blinking and grimacing under fluorescent light, 16-month-old Amanuel is here for the first time, and has been for just a few days. Brought in for diarrhoea, tests quickly revealed a more devastating diagnosis - HIV+, like both his parents - as well as associated tooth and jaw corrosion, and ominous patches of sores across his tender skin.

Paediatrics director Dr Wondewosen Desta sighs: “Nistartine would be the right drug for his oral problems, but it’s too expensive for us - we have to use a $2 oral gel instead, and hope for the best. It’s all so frustrating, for us and for the family. My friends are giving up their jobs - it’s too much, to see 50 or 60 per cent of your child patients with HIV. Most of them have repeated admissions. I have to be satisfied, just prolonging someone’s life a little. If we treat this child properly, he may make it to school one day. But more than one-third don’t get to celebrate their first birthday if we can’t treat them.”

Sometimes the gender roles are reversed - not often, but once or twice, here or there. Engeta Muhamed, 30, watches phlegmatically over toothily-grinning son Nudana, six years old but looking more like a baby, swamped inside regulation hospital green sleeves and rolling charming, cloying eyes at the camera. Engeta says his wife left him to bring up Nudana alone - a hard task anyway for a more-often-than-not unemployed labourer whose best daily wage would be $1.50, barely adequate for food and often forcing him to go begging instead.

“He’s still coughing, he’s not feeding well,” Engeta explains. “I know he’ll probably have to stay here for a month - after that, who knows? Of course I’m worried. I’ll have to leave my boy here and go out looking for work - but I can never earn enough. Every life’s like that here - everyone has to beg.”

Nor do the staff escape, both emotionally and physically - a flimsy, sloppily-slipped-on surgical glove, offering too little protection from cuts, or a grisly and deadly splash of blood to an eye: such accidents have ultimately claimed the lives of at least five workers in this department alone in recent years.

The illustrated children’s posters on the wall look merely sad, hopeless gestures: “Clean Face Prevents Trachoma” - “Let us make child vaccination our culture.”

Hopefully, a few rather more assuring signs of hope amid all the misery might, might just emerge over the coming days...

Tuesday, October 24, 2006

"Sail away with me, to another world..."

"News is what somebody somewhere wants to suppress - all the rest is advertising."

So, sagely, said Lord Northcliffe, and this is indeed the noblest of journalistic sentiments, a phrase that should ring in the ears, throb through the marrow and tingle through the fingers of any self-respecting journalist.

Sometimes, though, even the most high-minded will enjoy the benefit of an exaggerated expenses claim, a paid-for meal (or, better, bar tab), or the lucky dip of the freebie.

I remember well my first freebie: a box of Jane Asher cake mix, that sat at the back of my cupboard for months before I did the decent thing and handed it over to my mum.

Since then, I must confess to reading books, listening to CDs and - during one strange phase of unsolicited baskets - munching on my favourite Pink Lady apples and, er, red grapes. Oh, and the free football tickets have been muchly appreciated too, though more so for the likes of the World Cup final than an epic Coca-Cola Championship clash between Leicester and Hull.

Travel journalists, though, surely have the most easeful of occupations - I think it's safe to Judith Chalmers is a stranger to the Samaritans. Exhibit A, I offer the excellent and enviable Shandypockets pages, put together by one of those globe-gallivanting hacks we all wish we could/should have been.

In fact, we met on my one previous, dim-distant-past holiday blag, one that I am actually happy to accept as my one and only, such was the pinch-myself pleasure of the whole experience.

Of course, the obligatory plugs may chip away at what little credibility I might have had, but I tried to keep the plugs down to an appropriate minimum - yet also there where deserved. But, well, that's the game, innit...

It was a while ago now, but I was reminded to dig it out after pondering what to read next, after finally finishing "Jane Eyre" and swiftly dashing through "Monsignor Quixote" by Grahame Greene. On a similar Spanish tip (the Greene, that is, not the Currer Bell), I should really now get round to reading "Death In The Afternoon". After all...

I’ve always liked Islands In The Stream.

No, not the Ernest Hemingway novel, but the Dolly Parton and Kenny Rogers duet.

Yet it was the book I tipped off the shelves in preparation for a week in the Florida Keys, the sinuous strip of more than 800 islands separating mainland US from Cuba.

This tropical ribbon running through the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico promotes itself as Paradise, but is also classic Hemingway territory, a land of adventure and daring.

Think of Harry Morgan, the Key West maverick of Hemingway’s To Have And Have Not, sacrificing his morals, his arms and finally his life to run guns, liquor and wantaway Cubans across the waters.

Or Santiago, the decrepit hero of The Old Man And The Sea, battling the raging waters in his epic – and ultimately, excruciatingly vain – efforts to land the perfect marlin.

Or grizzled old “Papa” Hemingway himself, a-huntin’ and a-fishin’ and a-boozin’ and a-brawlin’ across the Keys and his favourite Key West haunts such as Sloppy Joe’s sloppy bar.

Or, of course, a dilettante English journalist like myself, visiting to enjoy a few massages, down a few cocktails and generally soak up the sun.

The macho Hemingway would no doubt disapprove of the luxurious spa resorts springing up across the Keys, nevertheless entirely suited to the location’s sun-drenched, laidback ambience.

Fror a start, a facial would surely do little for his ruddy, hardened complexion beneath those brutish bristles.

Yet after pitching up at the palatial Hawks Cay resort, with its immaculate villas, rich buffets and live dolphin show, it would have been rude not to sample the new spa centre of which they seem so proud.

Expecting myself to immediately switch off and shut down completely, hypnotically chanting “Om”, I assumed I was doing something wrong during the first facial.

Random, petty concerns kept popping into my still-buzzing brain: how will Spurs do this season, should I buy the latest White Stripes album, if we’re evolved from monkeys then why are there still monkeys...?

But soon I was sinking, pleasantly savouring the mysterious-yet-soothing oils, the warm blasts of air brushing my skin, the taped piano trilling gently in the background.

Yes, I could certainly get used to this type of treatment.

I finally floated out of the treatment room feeling like a new woman – I mean, man. I even tried to convince myself I was making a defiant statement of macho resistance by, er, not shaving.

But resistance was inevitably futile when a little bit of pampering could feel this great – Hemingway can just go fish.

A 50-minute Swedish massage the following day was even sweeter, leaving me a blissed-out hollow of a functioning man for the remains of the day.

The people of the Keys are clearly thrilled with their flourishing spa centres.

We were treated to a tour of the recently-built facility at Cheeca, the longer-established rival to Hawks Cay and favoured retreat of both George Bushes and family.

Sadly we were not there to samples the massage facilities, but made up for it by scoffing the cuisine – menu headed by the top local delicacy, Key Lime Pie, a sweet, light cheesecake.

The Florida Keys are not merely rich in terms of the landowners and well-heeled visitors (ourselves, of course, excepted).

The area’s wildlife is a source of consistent wonder. During a powerboat tour, we spied a lone dolphin frolicking in the shallows, while flutters of exotic birds circled above busy schools of tarpon and marlin below.

For the time being, at least, the many whales, sharks, manatees and turtles to be found in the depths were keeping their heads down.

Our guide explained the importance of the mangrove islands and the sea grass sustaining so much of the surrounding wildlife.

Damaging these plants can incur hefty fines for careless sailors, rising into millions of dollars. We kept a cautious, respectful distance.

An alternative insight into the Key creatures was found at Richie Moretti’s Turtle Hospital in Marathon.

If that name conjures up images of cartoon ninja critters sporting slings, bandages and plasters to accessorise their multi-coloured bandanas (well, it did for me), then the reality is a little more harrowing.

Here, 25-stone turtles, covered in vast tumours or showing off mutilated limbs, waded painfully in their shallow basins.

Richie bought the next-door motel in 1981, when this turtle hospital building was then a lap-dancing club called Fanny’s.

He funds the hospital entirely through the motel’s $200,000-a-year proceeds – a good example of Keysian economics, you might say. Or, indeed, might not.

As a committed veggie, I was not in a position to judge the overflowing, fresh fish platters thrust our way at every restaurant, including the lively Island Tiki Bar in Marathon or the Islamorada Fish Company in, well, Islamorada.

I was assured, though, of their excellence – and the portions would challenge even the hungriest Hemingway.

Probably the best meal we enjoyed, though, for both supplies and setting, was on the charmingly-named Pretty Joe Rock Island, a tiny seabound enclave owned by the Banana Bay Resort.

This hideaway is popular with honeymooning couples, and little wonder, with its luxury en-suite bathrooms, healthily-stocked kitchen and picturesque gardens.

After a tranquil two hours, within sight of the shore yet feeling care-lessly adrift from the world, we had to be dragged away.

Key West called – the southern tip of the US but where the Keys start to come to noisier life.

If I was feeling especially, generously patriotic, I’d describe it as like Brighton, only sunnier and hotter.

This is a bustling resort that prides itself on being a trendy, liberal party town – oh, and it rivals San Francisco for campness.

Certainly the delightful old colonial homes are more densely packed than in the Upper Keys, and the strong Cuban townships dating from the cigar factories’ 19th century heyday are full of character.

Visit El Masa de Pepe for sumptuous Cuban cuisine and an enthralling exhibition, sure to leave you whistling Guantanamera for days to come.

Our accommodation, the heritage-listed, late 19th-century Cypress House hotel, was an oasis of bohemian, classy calm.

The legendary main drag, seven-mile-long Duval Street, summons any self-respecting barcrawler – and again, for research purposes, I felt compelled to do my duty.

Anyone failing to realise Sloppy Joe’s was Hemingway’s favourite hang-out either has their eyes closed to the all-surrounding merchandise – or has knocked back one too many Mojitos.

Unsurprisingly, though, Key West’s finest attraction is nature itself.

Every evening at 6.30pm – yes, every evening – the sunset is celebrated with an exuberant festival on the shore.

Musicians, jugglers, trapeze artists, wizened old men pushing cats and dogs through bizarre hoops – all come out to play and greet the setting sun as it dips graciously, captivatingly into the sea behind Sunset Island.

This patch of land was originally known as Tank Island, but as the swanky condiminiums (condiminia?) multiplied, investors understandably opted for a more romantic-sounding name.

I watched the sun go down to the soundtrack of Mustapha, an ancient Jamaican busker plucking out simple, affecting versions of What A Wonderful World and Island In The Sun on his acoustic guitar.

The next evening we took an even better look, boarding Sebago’s Sunset Cruise, a two-hour voyage of simply sitting back, sipping champagne and watching the sunset at closer quarters.

A little sore-headed after such heady sights (and a few heady drinks), another massage – this time at the Pier House Resort and Caribbean Spa – couldn’t do any harm.

Nor could a leisurely tour of Key West’s quirkier tourist attractions, including the new-ish Butterfly and Nature Conservatory.

Careful where you tread, though, when exploring a tropical greenhouse habitat home to 1,200 vivid little winged wonders.

Of course, there is also Hemingway House, complete with smug ancestors of his beloved cats – and, not much farther on, a marker of the United States’ southernmost point.

In fact, you can also spot the southernmost house, the southernmost barber’s, the southernmost grocery store, the southernmost gallery, the southernmost horse being flogged...

I also enjoyed the Key West Shipwreck Museum, not just for the hammy antics of the historically-dressed tour guides, but also for the best aerial view of Key West – for those prepared to clamber the rigging, anyway.

The Old Town Trolley Tour is also essential, even if only to get your bearings and cherry-pick where to explore further.

Just be warned, though – our banter-loving guide’s best joke was: “Sorry about the bumps ahead in the next road. Though it’s not my fault, just as it’s not your fault. It’s the asphalt.”

(I laughed.)

Our final full day was taken up by something a little different, a trip to the newly-opened Walkabout Retreats venture, back towards Marathon.

The retreat is devoted to helping guests manage stress better, with “treatments” ranging from yoga, bike rides and kayaking to thick fruit smoothies.

Perhaps equally beneficial would be a meal at the ultra-stylish Hot Tin Roof restaurant – inspired by another noted Key West resident, Tennessee Williams, who perhaps could have been happier with his lot, all things considered.

Tucking into rich food and wine while overlooking the peaceful harbour was the perfect way to see out the Key West experience – though the following day’s 45-minute flight from Key West to Miami in a low-flying mini-jet had its photo-op merits, too.

A busy week, then – and yet a ridiculously-relaxed and relaxing one, at the same time.

It was no surprise to hear almost every Key West resident explain how they had moved there for good after visiting once on holiday.

That sounded perfectly reasonable to me – if not quite personally realistic.

Alternatively, of course, there are other Hemingway-inspired adventures to try.

Bull-fighting in Spain, after Death In The Afternoon?

Braving The Snows Of Kilimanjiro?

Hmm, maybe not for me just now, thanks.

After this, they sound a little too stressful.

Sunday, July 09, 2006

I'm all football-fatigued.

I feel well and truly Weltmeisterschaft-ed.

While I hope bits of "real life" have been sprinkled here and thereabouts during my last month or so of blogging, "normal service" should be resumed here shortly.

You have been warned, oh dear, dear, loyal reader(s)...

Nope, maybe I was right the first time.

"And I'll take a high dive, some day I'll never land..."

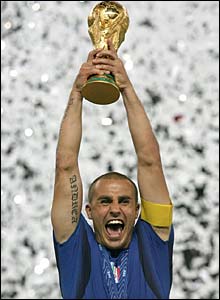

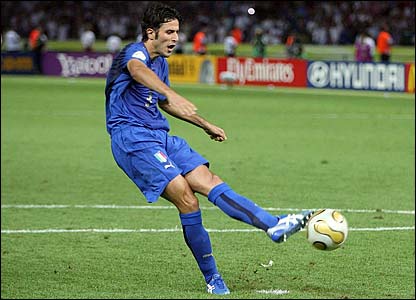

My voting slip, handed in half-an-hour before the deadline, opts for giving third place (one point) to Germany's Miroslav Klose, second place (three points) to Italy's Andrea Pirlo, and first place (five points) to Italy's Fabio Cannavaro.

That loud scratching sound you may have heard shortly before 10pm BST was caused by several hundred journalists simultaneously scoring a thick line through the words "Zinedine Zidane".

Cannavaro should now be a shoo-in, though Fifa's awards can still surprise.

A form just handed round the media centre reveals "The Most Entertaining Team award presented by Yahoo!", for the side "which has done the most to entertain the public with a positive approach to the game", goes to... Portugal.

Well, acting counts as a branch of entertainment, I suppose, but still...

"None shall sleep..."

"On the 31st floor, your gold-plated door won't keep out the Lord's burning rain..."

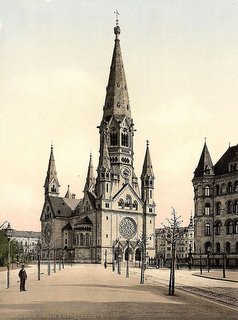

"The construction of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church is making such very good progress, the ignorant populace never cease to be amazed."

How charmingly-put by architect Franz Schwechten, writing in 1894 of the stately centrepiece of a vast church-building programme, lofted in unbashful tribute to the late Kaiser Wilhelm I on the orders of his grandson Wilhelm II.

And yet, after being battered by Allied bombs in 1943, the still-just-about-standing ruins have been transformed into a symbol, not of vainglory, but of humility - a ravaged reminder of the horrors of war, set in a self-sufficient square at the tip of the department store-dominated Kurfurstendamm.

The "broken tooth", as it's now nicknamed, is quite a sight - more raggedly beautiful now than in its once-epic glory, pictured in stills which suggest a neo-romanesque masterpiece suddenly plonked in lonely yet awesome isolation on a roundabout.

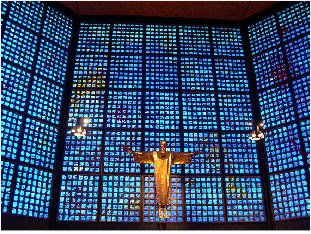

Inside stands a tiny, gleaming cross gifted by the similarly ill-fated, similarly defiant Coventry Cathedral - while the same cathedral has donated a cross made of nails to the now-next-door squat, decahedronal "replacement" church - where iris-dazzling cyan streams through tiny squares of stained-glass, and a grim-eyed, golden Christ tips awkwardly above the altar.

Inside stands a tiny, gleaming cross gifted by the similarly ill-fated, similarly defiant Coventry Cathedral - while the same cathedral has donated a cross made of nails to the now-next-door squat, decahedronal "replacement" church - where iris-dazzling cyan streams through tiny squares of stained-glass, and a grim-eyed, golden Christ tips awkwardly above the altar. The brief must have been: build something as different as can be, from what once stood - now totters - alongside. The effect of both is unnerving - yet touching too.

The brief must have been: build something as different as can be, from what once stood - now totters - alongside. The effect of both is unnerving - yet touching too.

"Tonight the bottle let me down..."

While I picked up a couple of tasteful(ish) WM2006 mugs, and a fascinating book (in helpful English and educative German) about East Berlin, the departed team souvenirs sat on shelves alongside bottles of wine that looked about as unappetising.

Yes, that's bottles of wine costing one solitary euro apiece - or about 70p.

Surprise surprise, I wasn't quite tempted to try - though I suppose the "wine" might at least go well on chips.

"But still the memory stays for always, my heart says danke schoen..."

Bad news from Berlin: thunderous monsoon-like downpours meant an open-air concert by musicians from 2010 hosts South Africa had to be cancelled.

Even worse – a James Blunt gig in the same city’s adidas "World Of Football" still went ahead.

But even his wailing went largely ignored as jubilant Germans seemed inclined to insist: third place is the new first.

From the Brandenburg Gate to the suburbs on the outskirts, from Saturday night’s final whistle to last night’s kick-off, this was a German party.

The stray clusters of Italian shirts or French tricoloures stood out shyly as tolerable impertinences.

Meanwhile the smoke smothering Berlin’s trendy Kurfurstendamm shopping drag wafted from makeshift fireworks.

But it seemed to have been sent all the way from Stuttgart and the ‘little-final’ third-place play-off.

Jurgen Klinsmann and his squad would follow, to lap up the rapture of 500,000 fans crowding the tumultuous "Fan Mile" this morning.

But not before Chancellor Angela Merkel, a pudgy Anne Robinson lookalike, had led that lop-sided awards ceremony in Stuttgart, a World Cup Weakest Link.

Germany - you win a set of shimmering bronze medals, a fireworks-and-lasers light fantastic, and the adulation of a nation.

Portugal – you leave with nothing. Goodbye.

Just one long month ago, the sight of swarming German flags and sound of soaring German anthems kicked off as many anguished national debates as they did backyard five-a-sides.

Yet this weekend there was no embarrassment at all as the Klinsi-inspired masses gridlocked the streets in celebration.

The odd alienated non-football fan would here and there give themselves away, by attempting a panic-stricken 27-point turn in search of a rare empty alleyway.

Strange, this European instinct to mark a footballing triumph, not by hitting the bars to get tanked up, but heading to their cars and tooting horns until tanked out.

Paris and Rome must both be on red, amber and green alert tonight, as both sets of blues duke it out here in Berlin (though France will be in white again tonight, as they have been for much of the tournament - even against port-red-clad Portugal. Surely the black-and-white-TV-viewing public isn't large and influential enough to have insisted "Allez les bleus" be replaced by "Allez les blancs"...?)

Ah, but anyway - the Germans have got in there first with the revelries.

Newspaper headlines and adverts are today proclaiming the German side Diana-sickly-style "Weltmeister unserer Herzen" – "World champions of our hearts".

As JFK might have said: "Wir sind alle Berliner" – and I don’t mean small, sticky doughnuts.

"And now, the end is near, and so we face the final curtain..."

I think I'll wait until then before deciding between Fabio Cannavaro and Zinedine Zidane, but here - for what scintilla it's worth - is my team of the tournament (for the time being...):

Gianluigi Buffon (Italy)

Gianluca Zambrotta (Italy)

Lilian Thuram (France)

Fabio Cannavaro (Italy)

Philipp Lahm (Germany)

Maxi Rodriguez (Argentina)

Andrea Pirlo (Italy)

Zinedine Zidane (France)

Maniche (Portugal)

Miroslav Klose (Germany)

Fernando Torres (Spain)

On the bench: Ricardo (Portugal), Rafael Marquez (Mexico), Willy Sagnol (France), Javier Mascherano (Argentina), Juan Roman Riquelme (Argentina), Ze Roberto (Brazil), Thierry Henry (France).

Odd how poorly strikers have performed this tournament, with a relatively meagre haul of five looking enough to reward Klose with the Golden Boot. Perhaps less surprisingly, there has been a dearth of obvious young stand-out starlets, leading to Lukas Podolski winning the best young player prize from Gillette, despite looking very raw and ragged in Germany's first two games, opening his account against half an Ecuador team already 2-0 down, then adding two easy-ish strikes against Sweden when Klose had done all the hard work each time.

At least he proved dangerous enough times when it mattered, whereas Cristiano Ronaldo merely looked like he might just prove dangerous most of the time (when not taking a jog along his invisible springboard, of course...)

"Temperatures rise as you see the whites of their eyes..."

Among the standard pre-season friendlies against the local likes of Stevenage, and such glamorous, unusual opponents as, er, only-recently-relegated Birmingham, Spurs have lined up a foreign jaunt that may just seem tempting: an August 5 match at Borussia Dortmund.

This evening, the Olympiastadion Berlin will become the tenth of the 12 German World Cup stadia I'll have visited for a match this summer (Hamburg and Leipzig are the two missing from my collection). Berlin may change my mind, but so far by far my favourite has been Dortmund.

The official Fifa guide to the tournament describes the Westfalenstadion as "the Bundesliga's Opera House". A nice description, but not really suitable, I would say. Maybe save that one for the imperious Munich or Stuttgart.

It's funny - or not, actually - to think about how the World Cup final tonight was 'supposed' to kick off at Wembley. Six years and £757million after England’s bid was rejected, Wembley still looks little more ready to stage the Brent WI’s summer fete.

For £213million more, Germany has kitted out 12 spectacular stadia fit indeed for this wunderbar World Cup – including Hanover’s ahead of schedule. Most expensive, £193million Munich is coated in “lozenge-shaped cushions’ that appear as an extra-terrestrial landing – or a giant gift with the wrapping left on.

In stark contrast, the steep banks of the Dortmund and Cologne terraces resemble old-fashioned Subbuteo-style grandstand constructions - only with more animation in the spectators, unless, perhaps, Switzerland are playing.

Like several, Dortmund's stadium has been temporarily stripped of standing areas – reducing capacity to a mere 65,000. But those sheer inclines, the sturdy right-angled roof contours, and the proximity of pitch to seats at least suggest all prawn sandwiches should be scoffed elsewhere. An anxious goalkeeper can almost feel the fans’ hot Bratwurst-scented breath upon his shoulders.

Greece’s German coach Otto Rehhagel has rued the trend for modern stadia to all roll off the same computer programme, sacrificing unique appeal. But there are quirks here to admire – from the five-star Gelsenkirchen’s retractable roof and pitch, to the Palatinate city vistas from Kaiserslautern’s lofty setting.

Stuttgart’s Gottlieb-Daimler-Stadion – wisely renamed from the Adolf Hitler Arena – offers rounded open, crisp-bowl terraces, rolling back from a pitch-distancing athletics track – plus Europe’s largest video screens. Perhaps these widest of wide-screen TVs are a response to Frankfurt’s 30-ton video cube, now with added dent courtesy of Paul Robinson.

Argentina’s urban choir, relentlessly chanting their ‘Vamos, Vamos’ anthem while pogo-hopping and flag-twirling, could still fire the emotions on a wet Wednesday at Underhill. But these 12 German Wembleys have done their bit beautifully. As even Phil Daniels could now concede: there might just be something to your Vorsprung durch Technik, you know.

But still, Dortmund - "the Bundesliga's Opera House"?

Not quite: the Bundesliga's Bear Pit, more like.

Wednesday, July 05, 2006

"I don't believe that he's the one - but if you insist, I must be wrong, I must be wrong..."

Could be – unless Mastercard belatedly come to their senses, that is.

All three were somehow chosen by Mastercard among the finest 69 performers at this World Cup, a selection to be whittled down to 23 today.

Bolton and Mexico striker Jared Borghetti also made the list – despite missing most of the first round through injury, then heading into his own net as Mexico fell to Argentina.

Whoever makes the squad, this could be Mastercard’s last.

They are furious with Fifa over a new sponsorship deal allowing rivals Visa to become ‘official partners’.

Mastercard’s image was tarnished by the 2006 ticket system, which denied card-holders with other firms the right to book online.

The confusion hardly reflected well on Fifa either - but Mastercard could now prove a convenient, if bitter, scapegoat.

Speaking of which, that well-known winker Cristiano Ronaldo is in the running for the Mastercard squad, and the Gillette-sponsored best young player prize.

But an internet campaign is trying to skew the online vote in favour of Luis Valencia.

For all his wing trickery, had Valencia actually been able to shoot then it could have been Ecuador not England facing Ronaldo and pals last Saturday.

Tuesday, July 04, 2006

"You've got a lot to answer for..."

And yes, he is German.

Yet in a nation which so prides itself on penalty expertise, Karl's profile has remained about as low as a Beckham corner failing miserably to beat the first man.

It was he, then a humble Bavarian referee at a local conference in 1970, who first suggested using a shoot-out to settle drawn matches.

Bavarian officials accepted the idea, the solution soon spread across German leagues, and eventually Uefa and Fifa were persuaded.

Yet Karl’s role in footballing history – and heartbreak – has gone unnoticed.

Until now.

He has finally emerged from the shoot-out shadows after his homeland celebrated yet another spot-kick success, this time on home turf.

Karl, now 90 and a referee since 1936, is unapologetic - despite the incessant despair, and Pizza Hut adverts, he has helped inflict on the English.

He insisted: ‘I always believed I was right.

‘It’s the only way in which a result can be achieved fairly. Everything else was not really a solution.’

He may just have a point there.

The previous system, involving a tossed coin or coloured disc, left even more to chance.

A wrong call knocked Yugoslavia out of the 1968 European Championships after a semi-final stalemate against Italy.

Former Liverpool manager Bill Shankly once went typically apoplectic to discover captain Ron Yeats was denied a choice of head or tails after a Fairs Cup draw with Cologne in 1968

The referee presented a disc with Liverpool red on one side and Cologne white on the other.

Affter the spin went against his side, Shankly angrily insisted on his right to call white if he wanted – to no avail.

Of course, Liverpool went on to benefit from the spot-kick system in last year’s epic Champions League triumph over Milan.

So perhaps, rather than condemning Karl, English fans should grudgingly accept his belated moment of fame.

After all, if our cricket captains’ coin-tossing luck is anything to go by, these 40 years of footballing hurt could have been equally excruciating either way.

Of course, meine Damen und Herren, it only works if you manage to see out 120 minutes without conceding, not a mere 119...

Sunday, July 02, 2006

"It is so long a chain, and yet every link rings true..."

The Blue Carbuncle, the Engineer's Thumb, the Twisted Lip, the Yellow Face - the Red Headed League, the Reigate Squire, the Norwood Builder, the Speckled Band... these and all 51 more have all perplexed, intrigued and finally illuminated me, even as the smudge-covered, dusky-coloured hardback weighed down what should have been more dully-useful holiday luggage over the years...

The Blue Carbuncle, the Engineer's Thumb, the Twisted Lip, the Yellow Face - the Red Headed League, the Reigate Squire, the Norwood Builder, the Speckled Band... these and all 51 more have all perplexed, intrigued and finally illuminated me, even as the smudge-covered, dusky-coloured hardback weighed down what should have been more dully-useful holiday luggage over the years...... but for all my entrancement in my old-fashioned compilation of every short story, every charming pencil-black original illustration from The Strand magazine, every frustrated attempt to make progress in the impossibly-complex Spectrum 128k computer game, every visit to that famous address either in passing or in museum-exploring pilgrimage, every rippingly-antiquated shards of awkward dialogue and every seamily glamorous glimpse of London Victoriana...