Occasionally, just occasionally, amidst all the everyday trivialities, my job allows me to feel some (very) small involvement in something worthwhile. Last Friday I travelled to the Holocaust Centre, in the middle of Nottinghamshire-nowhere, to speak to a survivor of the Rwandan genocide who, following a story I wrote last December, has finally been brought to Britain for - hopefully - life-saving, transforming surgery.

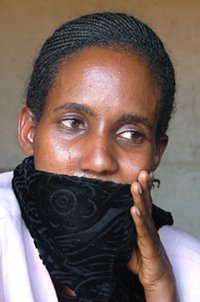

Occasionally, just occasionally, amidst all the everyday trivialities, my job allows me to feel some (very) small involvement in something worthwhile. Last Friday I travelled to the Holocaust Centre, in the middle of Nottinghamshire-nowhere, to speak to a survivor of the Rwandan genocide who, following a story I wrote last December, has finally been brought to Britain for - hopefully - life-saving, transforming surgery.Odette Mupenzi - half her face blasted away by gunmen and now shrouded under a thick black scarf, her spindle-thin body shivering and tottering in the British chill - has suffered 12 years of agony, which can hopefully now be redeemed thanks to the efforts of determined charity workers, generous public donors - and her own astonishing fortitude...

A bit of a humbling experience, really...

A YOUNG woman whose face was shot away in the Rwandan genocide has arrived in Britain hoping her nightmare will soon be over.

Odette Mupenzi will this week start the surgery which could free her from pain and give her a new face - thanks to Metro readers.

Their donations could now pave the way for many more casualties of the genocide to receive life-changing help and treatment.

The 30-year-old Rwandan, wracked by starvation and infection, was brought to Britain after a Metro appeal helped raise more than £50,000.

As she prepares for a long-awaited lifeline, Odette said: 'I'm so grateful to everyone who's helped. I want to thank every one.

'I didn't think I would ever get well again - then I saw all these efforts people are putting in, which have made a big big difference. Now I have hope.'

Odette was horrifically disfigured when Hutu militiamen burst into a school where she and her family were hiding in 1994.

She saw her father hacked to death by two soldiers and old friends who betrayed the family, while her mother was beaten and had an ear sliced off.

One of the troops found Odette and fired a barrage of bullets into her jaw, arms and chest, before the whole gang hacked at her with machetes.

Somehow she survived, and was found among the corpses by one of the religious brothers running the school.

A courageous Hutu doctor helped her escape to a hospital where her infected wounds were dressed and she was fed a paste of milk and biscuits through a syringe.

But attempts to restore her face, with trips to Switzerland, Germany and South Africa, all foundered for lack of funds.

Charity workers fear she could soon die due her to plummeting weight and frequent infections in her wounds.

She cannot eat properly through his misshapen mouth, and suffers constant headaches and spinal pain.

When the Aegis Trust and Metro appealed for help last December, it had been hoped that £10,000 might be raised.

British charity the Pears Foundation had promised to double funds to £20,000.

But within days, Metro readers had rushed to pledge more than £25,000 - ultimately pushing the Odette fund beyond the £50,000 barrier.

A special fund has been set up in Odette's name, and the Aegis Trust hopes the money will pay for both her treatment and many more projects.

Ian Hutcheson, one of the UK's most respected facial surgeons, is heading a team of London-based specialists who have been studying Odette's plight and planning the best response.

After struggles to win a visa, Odette has now been given permission to stay in Britain for up to six months - and is being looked after by Aegis in the Nottinghamshire countryside.

She is being kept on a careful diet of nutritional supplements to build up her strength - but her only concern at the moment is the cold British weather.

'I'm having to wear two thick jumpers at the moment, but I hope I'll get used to it,' she said.

Odette insists she would rather die than suffer again at the hands of her attackers, who are now back on the streets of still-divided Rwanda.

Twelve years after the 100-day slaughter which claimed 1million lives, tensions between Tutsis and their Hutu slaughterers remain tense.

Odette is forced to relive her harrowing ordeal every day, thanks to the taunts of neighbours - and the fact she lives just across the road from the scene of the brutality.

Above all, she fears a reunion with her attackers - knowing many have been given early releases from prison as part of troubled Rwanda's attempts at reconciliation.

Odette bravely gave evidence against one of the former friends who mutilated her then left her for dead, helping convict and imprison him.

But she knows he and others are now out of jail - and could run into her at any moment.

She said: 'The greatest fear is that he could come and hurt me again.

'If I died, it would be okay, because I wouldn't be in pain anymore.

'But if he came to hurt me again, and I got more injuries, I wouldn't be able to bear it.'

Odette and her mother live just 100 metres from the school where their family was brutalised, and just across the road from the former home they tried to flee.

She regularly bumps into the estranged wives of some of her assailants.

'They point at me over fences, and sometimes they shout and insult me,' she said.

'There's not a day goes by when I don't think about what happened. I can't escape.

'People want to forget what happened - they don't talk about it, they try to deny the genocide. But it still hurts.

'If I could, I would gladly leave the place behind and never go back - but there's just no way for that to happen right now.'

Odette, her mother and a younger sister live in a three-roomed shack, with a roof barely worthy of the name.

Odette's dreams of a nursing career were shattered by the attack, and she spends her healthier days only able to do the odd bit of housework.

Danielle Mbesherubusa, who accompanied Odette to Britain, said: 'I really don't know how that family survives. They have barely any income at all.'

The Rwandan government has set up a fund for genocide survivors, knowing many young people were orphaned and traumatised.

But their focus remains more on the country's slowly-burgeoning economy, according to Odette's friend Danielle Mbesherubusa.

Danielle runs the Aegis Trust's social welfare programme in Rwanda, helping families with transport, food.

She said: 'Sometimes we're able to give a family £10 or £20 a month - and to them, that's huge. It means so much to them.

'It's easy to think the genocide happened 12 years ago and is over now, but the consequences won't go away that easily.

'So many people lost their childhoods and any opportunities to go to university and make something of themselves.

'The trauma they've gone through is bad enough, without all the financial difficulties so many are now suffering.'